A new study suggests that the people put to death in America are hardly the worst of the worst offenders.

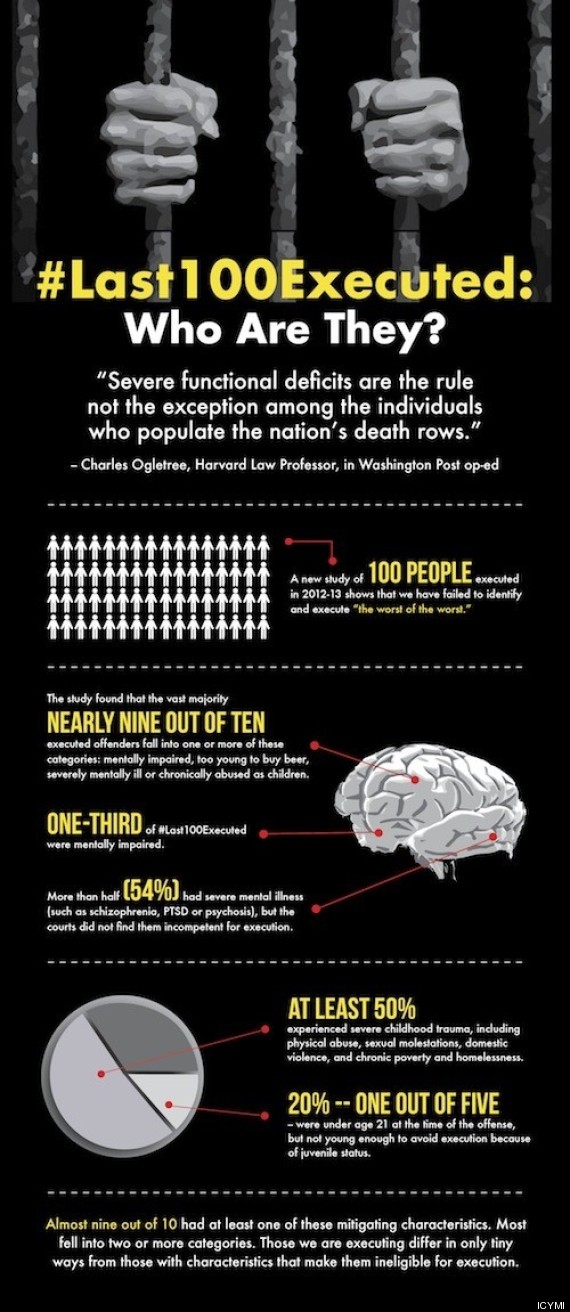

The study, published in Hastings Law Journal, looked at 100 executions between 2012 and 2013. Some of the most striking results are displayed in the graphic.

Story continues below ...

Robert Smith, the study's lead researcher and an assistant professor of law at the University of North Carolina, told The Huffington Post his research provides evidence that many of the people who are actually put to death are not cold, calculating, remorseless killers.

"A lot of folks even familiar with criminal justice and the death penalty system thought that, by the time you executed somebody, you’re really gonna get these people that the court describes as the worst of the worst," Smith said. "It was surprising to us just how many of the people that we found had evidence in their record suggesting that there are real problems with functional deficits that you wouldn't expect to see in people being executed."

One of the people in Smith's study is Daniel Cook. Cook's mom drank and used drugs while she was pregnant with him. His mother and grandparents molested him and his dad abused him by, among other things, burning his genitals with a cigarette.

As Harvard Law Professor Charles J. Ogletree, Jr. documents in the Washington Post, Cook was later placed in foster care, where a "foster parent chained him nude to a bed and raped him while other adults watched from the next room through a one-way mirror."

The prosecutor who presented the death penalty case against Cook said he never would have put execution on the table if he had known about the man's brutal past. Nonetheless, Cook was put to death on Aug. 8, 2012.

In various landmark cases, the Supreme Court has found that executing people with an intellectual disability or severe mental illness can be a violation of the Eighth Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment.

The court has also found that severe childhood trauma can be a mitigating factor in a defendant's case, according to a press release accompanying the report.

But Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, said there are serious flaws with the study's methodology. He noted that the authors count someone as intellectually disabled if they score below a 70 on at least one IQ test. However, he said, looking at the lowest score in a series of tests can be misleading.

"How fast can you run a mile? If you run on several different days and have several different times, the speed at which you can do it is your fastest time," Scheidegger said in an email to HuffPost. "Various factors can make you perform less than your best, including simply not trying hard, but nothing can make you perform better than your best. It's the same with IQ scores. The high score is a good indication of performance. The low score means practically nothing."

Scheidegger also said mitigating factors like intellectual disability or a traumatic childhood don't matter nearly as much as the brutality of the crimes that death row inmates have committed.

"Since 1978, defendants have had carte blanche to introduce everything including the kitchen sink in mitigation," Scheidegger said. "The actions of their attorneys in finding and presenting that evidence is scrutinized repeatedly in the years after the trial. What we see in case after case is that even after years of reinvestigation and relitigation, the horrifying facts of the crime remain far more than sufficient to outweigh the minimally relevant evidence in mitigation."

But Smith said the courts have found that, independent of the heinousness of the crime, the prosecution must also show that the defendant is "morally culpable."

"The Eighth Amendment requires that the death penalty be limited in its application to only those offenders who commit the most aggravated homicides and who possess the most aggravated moral culpability," Smith said.

"But our research showed that of the last 100 people we executed in America, most of them had severe functional deficits. In many cases, they suffered from several mental illness and years of horrific abuse. And the problem is that there is no standard measurement for these type of functional deficits. For instance, there is no IQ score equivalent for gauging the functional deficits that mark any particular person with a severe mental illness."

Smith also said those who ended up executed did not have adequate representation at the trial level. Juries were often not informed of defendants' intellectual or mental health problems or their family history of extreme abuse.

Smith noted that the reason traumatic childhoods are brought up is not necessarily to make juries feel bad for the person on trial, but because "decades of research" has shown that these types of trauma can trigger the kinds of "functional deficits" that were present in many of the cases examined in the report.

"We’re executing people who get the worst lawyers, have the least resources and are the most vulnerable," Smith said.

Sometimes these mitigating factors come out during the appeals process, but by then it may be too late, since judges often give deference to the jury's verdict.

"It's often a tale told too late," Smith said. "How many of these people would have not even come close to dying if they had had good lawyers at trial or pre-trial?"

With executions either being outlawed or rarely used in many parts of the country, Smith said the punishment's days may be numbered.

"We're not talking about reform," Smith said. "We're talking about it being on its way out."