Lawyers for Andre Thomas—the young Sherman man who stabbed to death his ex-wife, his young son, and an infant; cut out the children’s hearts and put them in his pockets; gouged out his right eye after getting arrested; and, after being convicted of murder and given the death penalty, gouged out his left eye and ate it—will be arguing his case before a panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals on Tuesday. They’ll get thirty minutes to make their case that Thomas, who suffers from severe mental illness, deserves an appeal before the full federal court. If successful, he will get it. If not, Thomas will be one step closer to execution.

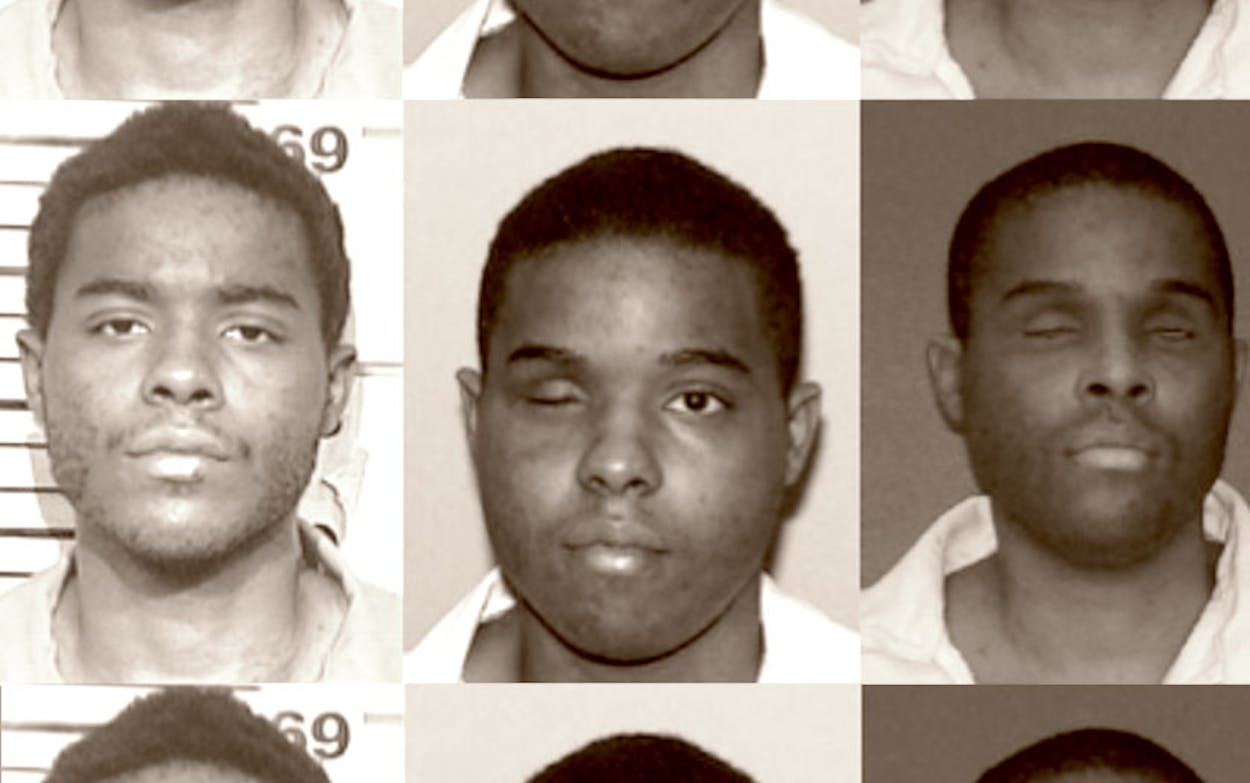

This unbelievably tragic and complicated case—which Brandi Grissom wrote about for Texas Monthly in March 2013—has been winding through the courts since March 2004, when Thomas, then 21, slew his ex-wife, Laura Boren, their son, Andre Jr., and Leyha, her baby daughter by another man. Thomas is black, Laura was white—which would end up playing a role in Thomas’s trial.

Thomas had a long history of mental illness; he heard voices in his head from age nine and began trying to kill himself soon after. He grew up poor with an alcoholic father and mentally ill mother, and early on began smoking weed and drinking alcohol. This behavior continued through his teen years, when he dropped out of school but also worked steady jobs, and eventually fathered Andre Jr., and married Laura. In the months before the murders, Thomas’s behavior got more and more bizarre—putting duct tape over his mouth for days at a time (because God told him not to talk), hearing the voices of God dueling with the voices of demons. He began supplementing his weed and alcohol with large quantities of the cold medicine Coricidin, which can cause a sense of euphoria. And he continued to cut and stab himself. In the month before the murders he was taken to both a mental health clinic and a hospital because of suicide attempts, but each time he left before he could get any treatment.

The barbarity of the murders shocked the small city of Sherman, just north of Dallas, which had never beheld a crime like this. Why, everyone asked, would someone do this? “I thought it was what God wanted me to do,” Thomas told law enforcement. Then, five days after the murders, he was sitting in jail reading the Bible and came across Matthew 5:29. “If your right eye causes you to stumble,” he read, “gouge it out.” So he did. Thomas was evaluated by three psychologists, who found he was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and was therefore not competent to stand trial.

But Thomas was sent to a mental hospital, where after six weeks of treatment with meds and therapy, he changed. Now a psychologist, who thought Thomas was exaggerating his symptoms, altered his diagnosis to “substance-induced psychosis.” Most important, Thomas was now judged competent to stand trial.

Proceedings began in February 2005. While Thomas’s lawyers never denied that he had committed the murders, they argued he should be found not guilty because his mental illness prevented him from knowing right from wrong. In other words, he was crazy. The prosecution said he wasn’t crazy, he was high—and that his psychosis was either caused by his drug and alcohol abuse or made worse by it. Ultimately, they said, Thomas knew right from wrong. The all-white jury agreed, finding Thomas guilty and sentencing him to death.

Thomas was sent to death row at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, where he continued slashing his throat and wrists. Finally, in December 2008, he gouged out his remaining left eye. Then, he did something really crazy: He ate it.

Should we be trying to execute someone who would do that, a man with a severe mental illness, psychosis, and maybe schizophrenia?

That depends on who you talk to. The U.S. Supreme Court has, over the last sixteen years, carved out some notable exceptions to those individuals the state can execute: juveniles, the intellectually disabled (those who used to be described as “mentally retarded”), and the insane—those with no idea of right and wrong or why they are being punished with death.

But there are no such prohibitions on executing the mentally ill—for example, people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, extreme paranoia—and we do it all the time. Georgia recently executed a cop-killing war veteran with PTSD, Florida a mass murderer with schizophrenia. Dylann Roof, convicted of murdering nine churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, in June 2015, was diagnosed by a psychiatrist as suffering from “Social Anxiety Disorder, a Mixed Substance Abuse Disorder, a Schizoid Personality Disorder, depression by history, and a possible Autistic Spectrum Disorder.”

How do we determine if someone’s mental illness is so severe as to cross over the line into insanity? The Supreme Court has said that if an inmate has a “rational understanding” that he is being executed because of his crime, he is sane enough to be executed—and Texas courts, including the Court of Criminal Appeals, generally have found that most mentally ill defendants knew what they were doing. That was the court’s thinking on Thomas, about whom CCA judge Cathy Cochran summarized in March 2009, “This is a sad case … Applicant is clearly ‘crazy,’ but he is also ‘sane’ under Texas law.”

Thomas’s lawyers have so far lost at every step of the appellate way, in both state and federal courts. To get the most recent denial (that of the federal court) reviewed, he needs to get a Certificate of Appealability (COA) from the Fifth Circuit. And his attorneys need to win over the three judges in the panel at the oral arguments. This will be easier said than done; one of them is the conservative, pro-death penalty jurist Edith Jones.

Thomas’s lawyers will argue what they outlined in their brief: that he didn’t know right from wrong and is too mentally ill to be executed. They’ll also argue that the jury was racially biased—three jurors told the court they were against interracial marriages like the one Thomas had been in (one said he was “vigorously” opposed: “I don’t believe God intended for this”). Finally, they’ll argue that Thomas’s trial lawyers were constitutionally ineffective, failing to fight the change in his competency ruling, failing to try to keep the anti-mixed-marriage jurors off the jury, and failing to compile much evidence about Thomas’s mental illness and hard-luck upbringing at the punishment phase of his trial.

The lawyers are also asking the high courts to finally declare the end of the death penalty for the mentally ill, arguing that the constitutionally accepted justifications for capital punishment—retribution and deterrence—don’t work for the mentally ill and their “diminished moral culpability.” Also, the brief argues, “There is a growing consensus against the execution of the severely mentally ill. The leading legal and mental-health professional organizations—including the American Bar Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Psychological Association—oppose the death penalty for the severely mentally ill.”

The state’s brief argues Thomas was a manipulative, violent juvenile delinquent who knew right from wrong and whose psychosis was induced by drug and alcohol abuse. The state downplays the influence of the views of the three jurors and points out that both of Thomas’s lawyers testified that they thought their client was competent to stand trial. And as for the sea change in the law sought by Thomas’s lawyers: “The Fifth Circuit has consistently refused to find a connection between the intellectually disabled and the mentally ill, repeatedly rejecting arguments like the one Thomas makes now, and indeed, Thomas provides no basis for reversing course.”

Federal appellate courts tend to grant only about 20 percent of oral argument requests—so this hearing could be a good sign for Thomas. Former CCA judge Cochran, who has a lot of experience with the Fifth Circuit, thinks that the court agreed to hear the arguments because it is interested in a particular aspect of Thomas’s case and wants to give the lawyers the opportunity to flesh out their positions. “It’s probable that the issue they’re most interested in is the one dealing with racial bias after the recent Supreme Court case out of Georgia, Tharpe v. Sellers, which sent that death penalty case back to the lower courts to examine more closely the alleged racial bias claim in light of the Court’s earlier decisions in Buck, Pena-Rodriguez, and Foster v. Chapman. I think that the Fifth Circuit is probably sensing which way the wind is blowing in deciding whether to grant a COA [Certificate of Appealability].”

If the court grants it, Thomas’s case will eventually be considered in detail by the Fifth Circuit, and both sides will file briefs all over again. If the court denies it, he will have one final place to go: the U.S. Supreme Court.

Thomas isn’t actually living on death row in Livingston. Since he gouged out his second eye, he’s been incarcerated at the Beauford H. Jester IV Unit, a psychiatric facility in Fort Bend County. He won’t go back to death row until he gets a date with the executioner. This is not out of the question, even these days when Texas, like other states, is seriously ratcheting back its use of the death penalty, from a high of forty executions in 2000 to seven last year. Judges, politicians, and law enforcement personnel have shown no indication that they would hesitate to execute someone they think deserves it—even a blind psychotic.

- More About:

- Death Penalty

- Crime