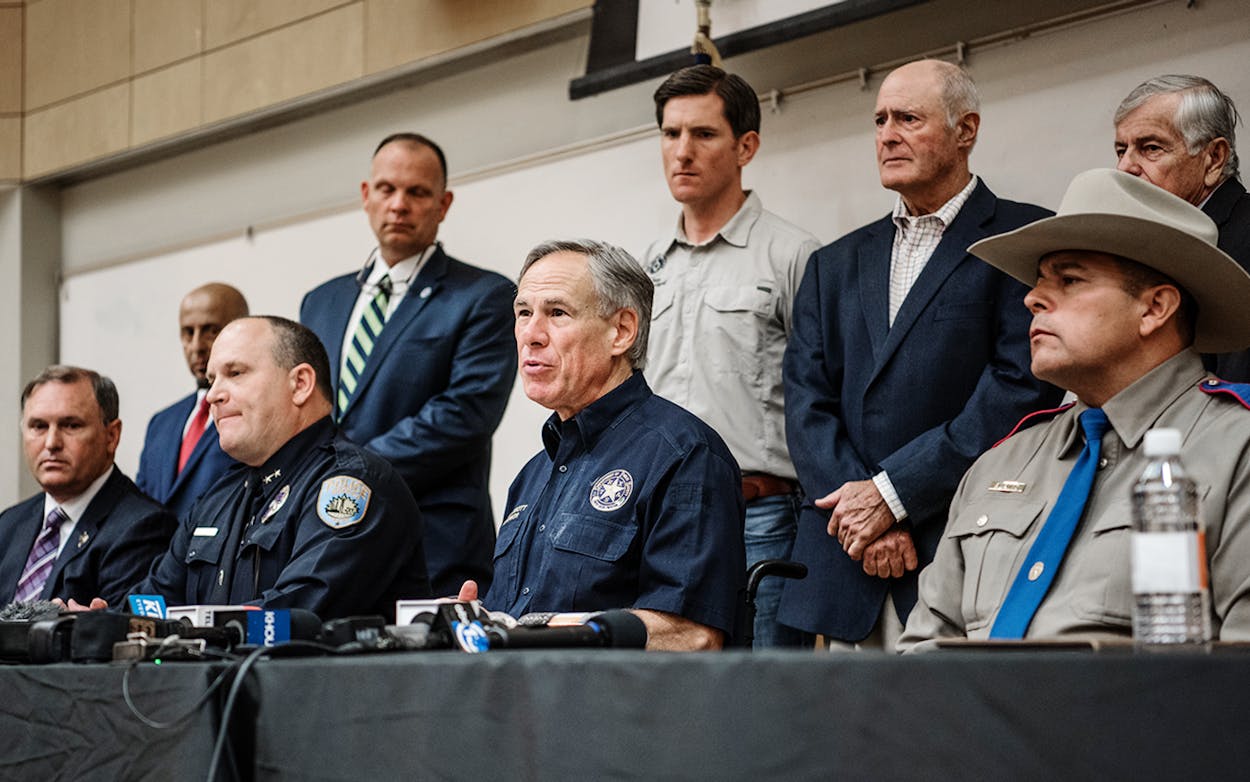

Governor Greg Abbott tweeted last week that “expedited executions” for mass shooters would make a “nice addition” to the package of policy proposals he was assembling in the wake of massacres in El Paso and Midland-Odessa. It was a curious proposal, as my colleague Dan Solomon noted, given that two of the four most prolific recent shooters were killed in their attacks, the third is too young to be executed, and the fourth had previously expressed a desire to die as soon as possible. But it was also a reminder that the death penalty retains a strong psychic hold on ideas about justice and public safety, even as capital punishment has evolved to become more and more, at least in the United States, a singularly Texan institution.

The use of the death penalty has slowed precipitously across the U.S. Only thirteen states have executed anyone since 2013. Last year, just eight states had an execution, and Texas was responsible for more than half of the total number nationwide. Though the pace has slowed even here, Texas’ death penalty machine is still chugging along. The state’s next execution is scheduled for September 10, followed by one on September 25. Four more are scheduled for October, followed by another four through the end of the year. There are 218 people on death row.

Abbott’s statement implied that execution is a just reward for a mass murderer, but also that it would deter others from similar atrocities. That’s been the historic intention behind the death penalty—showy warnings, in the form of crucifixions, drawing-and-quarterings, burnings at the stake, hangings in the town square. But that’s not the case in Texas anymore. In some ways the death penalty in Texas has never been more grotesque—more bureaucratic, more antiseptic.

Last month, the state of Texas executed Larry Swearingen, a 48-year-old man from Montgomery County. In 1998, Swearingen raped and murdered nineteen-year-old Melissa Trotter, then a friend and college classmate. Or maybe he didn’t. No biological evidence ever tied Swearingen to the killing, and there’s plenty of reason for doubt if you’re looking for it, as laid out in this Washington Post summary of his defense team’s counterclaims.

Perhaps most significantly, a succession of forensic pathologists and others testified that Trotter seemed to have been killed after Swearingen had been arrested and was waiting in jail—which, as alibis go, is pretty good. Prosecutors, of course, think all that’s hogwash, and Trotter’s parents are convinced of Swearingen’s guilt too. They have their own set of compelling evidence and a record of things Swearingen did after he was arrested that imply guilt.

They may well be right, of course. We don’t know for sure, and we will likely never find out. We do know that a truly unimaginable thing happened to Trotter. “A bad man got what he deserved tonight,” said prosecutor Kelly Blackburn, claiming vengeance. “Larry Swearingen needs to be removed from the annals of history as far as I’m concerned.”

It’s a curious turn of phrase: removed from the annals of history, as if Blackburn were a censor in a bureaucrat’s office instead of a prosecutor. What Larry Swearingen leaves behind in the annals of history, as the excellent Keri Blakinger of the Houston Chronicle pointed out on Twitter, is paperwork:

Just got here to Huntsville a little bit ago – here’s the schedule as to what Larry Swearingen did in the past 3 days. He talked to a Texas Ranger, got visits from friends, refused breakfast this morning – and cleaned his toilet. pic.twitter.com/id0EkZpIDf

— Keri Blakinger (@keribla) August 21, 2019

Here’s the official timeline of the execution: pic.twitter.com/0qzouIXsg8

— Keri Blakinger (@keribla) August 22, 2019

I had never seen these forms before. They’re remarkable, above all else, for their banality. They’re what you get when you make killing boring, like combining murder with the DMV.

The first set of documents, the “Death Watch,” contains the careful notation of how citizen Swearingen spent his last 72 hours. After midnight, he stood at the door of his cell talking, then went to a desk to write. He packed up his belongings, to save someone the trouble, and presumably for the same reason, he cleaned his toilet too. (Blakinger’s podcast interview with Swearingen is worth a listen—among other things, he describes the way prisoners on death row make their own Magic: The Gathering cards, shouting plays at each other through the door.) On the last day, the notes stop abruptly. They’re no longer needed.

The second document is much stranger. The “Execution Recording” for prisoner No. 999361 picks up some time after the first document leaves off. It looks indistinguishable from every dumb government form you’ve ever filled out, from the Times New Roman type to the blanks made with the underline key to the office fax number at the bottom. On here, state employees record that Swearingen was “STRAPPED TO GURNEY” at 6:23. At 6:35, the “LETHAL DOSE BEGAN,” and seven minutes later, a time was registered for “PROCESS COMPLETED.”

The comments section is blank. Apparently nothing about the day’s events seemed worth mentioning. Swearingen kept his own record. “I can hear it going through the vein—I can taste it,” he said. There was a burning sensation in his right arm, something others executed have mentioned as well. Eventually, he started snoring.

I’d much rather be shot. Wouldn’t you? Death by firing squad seems more honest and might even involve less pain than this bizarre pseudo-medical ritual. But because the Supreme Court held that the Constitution’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment” implies a directive to minimize “unnecessary pain,” states settled on a lethal injection process that puts prisoners to sleep before stopping their hearts. Pharmaceutical companies won’t sell the necessary drugs to Texas, however, so the state uses home-brew, locally-procured substitutes. And it all happens in private, so that the public can be spared the indignity of watching.

Part of the desire to make it a rigid, clinical process, of course, is that state employees must be involved in the government’s state-sanctioned killing—a cruel thing, even if they volunteer for it. The result is something strange and alienating. In the replies to one of Blakinger’s tweets, a former Houston Chronicle reporter commented that “Texas excels at making executions workaday affairs. I covered one for the Houston Chron many moons ago. When it was over, a guard said, ‘That was a quick one,’” she wrote. “And then we went to the communications [director]’s office to write our stories while he watched Wheel of Fortune.”

Even the little traditions that used to connect the old death penalty to the new one are being rolled back. In 2011, Texas ended the practice of serving convicts a last meal of their choosing before their execution, after one person ordered a large meal he didn’t eat—a trivial expense. And there was pressure during the most recent legislative session to end the practice of reading convicts’ last remarks to the media. (Both originated with pressure from state senator John Whitmire, a Democrat.)

Conservatives tend to support capital punishment more than liberals, even though government is never bigger than when it’s flushing poison through someone’s veins. If the state can’t be entrusted with tax dollars, how can it be trusted with the ability to decide which of its citizens deserve to die? When France abolished the death penalty in 1981, it did so because, as Francois Mitterand’s justice minister argued, executions create a totalitarian relationship between the state and the individual. “The true political signification of capital punishment is that it results from the idea that State” owns its people, he said.

Free countries tend not to employ the death penalty—unfree countries do. Today, the world leader in executions is China. Human rights organizations believe that the Chinese state kills thousands each year, some of them in mobile “execution vans.” The Chinese executioners in the vans use the American three-step lethal-injection process, first demonstrated in 1982, in Texas.

After Swearingen died, a prison official closed out the process at a press conference. The event of the day “was the twelfth execution in the United States this year, the fourth in Texas, and there are eleven additional executions scheduled between now and the end of this calendar year,” he said. “Any questions?”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Death Row

- Death Penalty

- Greg Abbott