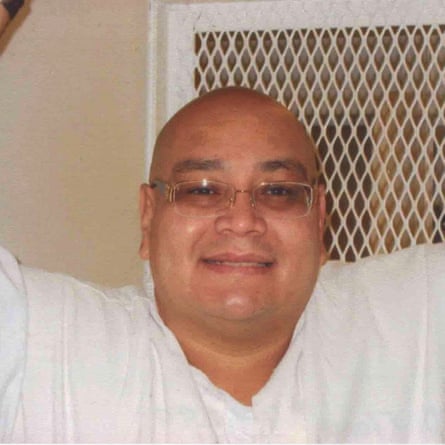

In January 2016, Charles Flores, a Texas prisoner, was moved to death watch, where inmates awaiting execution spend their final months. Seventeen years earlier, Flores had been convicted of murdering a woman in a Dallas suburb in the course of a robbery, a crime he says he did not commit. All of his appeals had been denied and his lethal injection was scheduled for 2 June.

Flores’s new neighbour on death watch, who was due to die in two weeks, gave him the name of his attorney, Gregory Gardner. Gardner specialised in fighting capital punishment convictions and had helped this man take his case to the US supreme court. Flores wrote to Gardner, telling him about the troubling course his trial had taken. No physical evidence had been presented to tie him to the murder, his defence had failed him in multiple ways and, perhaps most troublingly, the only eye witness who claimed to have seen him at the scene of the crime had been hypnotised by police during questioning.

Hypnosis has been used as a forensic tool by US law enforcement and intelligence agencies since the second world war. Proponents argue that it allows victims and witnesses to recall traumatic events with greater clarity by detaching them from emotions that muddy the memory. In the case that led police departments across the country to begin using forensic hypnosis, a school bus driver in California, who had been abducted and buried alive with 26 students in an underground trailer, later accurately recalled most of the licence plate of his abductors while under hypnosis. (All 27 captives survived the ordeal, after they dug themselves out of the trailer with a piece of wood.)

That was in 1976. In recent decades, the scientific validity of forensic hypnosis has been called into question by experts who study how memory operates, especially in police interviews and courtrooms. It is one example of a growing number of forensic practices – including the analysis of blood spatter patterns and the study of what distinguishes arson from accidental fires – that prosecutors once relied on to secure convictions, but which are now considered to be unreliable. “The breadth of scientific error in forensic disciplines is breathtaking,” Ben Wolff, an attorney for Flores, told me.

After reading about Flores’s case, Gardner got in touch with a hypnosis expert named Dr Steven Lynn. As a young psychologist in the 1970s, Lynn was a “true believer” in the power of hypnosis to retrieve memories, he later testified in a hearing in Flores’s case. But when Lynn began to test this assumption, he found that in study after study, hypnosis actually harmed subjects’ recall. It led them to “recover” at least as many false memories as accurate ones, while increasing their confidence in the memories’ accuracy. “Maybe they’re having a very vivid experience during hypnosis, but that experience is not necessarily a truthful experience,” Lynn told the court.

After contacting Lynn, Gardner filed an appeal before the highest criminal court in Texas. He based the appeal on a law passed in Texas three years earlier, in May 2013, known as the junk science statute. Among other things, the statute held that convictions could be thrown out if it was shown that they relied on discredited or misused scientific evidence. It was the first law of its kind in the US and a major step forward for fighting wrongful convictions – but it had not yet been tested in a forensic hypnosis case. “It felt like we were at the casino and pushing all the chips in,” Flores said.

In an affidavit included with Flores’s appeal, Lynn wrote that “a significant development in the study of psychology over the past two decades or so has been the decline and fall of the idea that memory is a vast, permanent and potentially accessible storehouse of information.” In a subsequent hearing, Lynn testified that the hypnosis in the Flores case had relied on this faulty concept of memory and that it may have contributed to the witness’s confidence in her testimony. At trial, the witness had said she was “over 100% positive” that she saw Flores at the crime scene.

On 27 May 2016, six days before he was supposed to be put to death, the court granted Flores a stay of execution and sent the case back to a lower court for review. In October 2018, that court affirmed the original conviction, which means Flores is still on death row. He is now waiting for his final appeal to be heard by Texas’s highest criminal court.

His case, along with another, similar case from Texas, could determine the future of forensic hypnosis in the state and across the country. Since 1987, the supreme court has held that information and testimony from hypnotised witnesses cannot automatically be thrown out of court. Texas is one of 13 states that allow hypnotically induced testimony, as long as the hypnosis is carried out according to certain guidelines; a further four states permit it unconditionally. Of these 17 states, 10 also have active capital punishment laws, which means they can put potentially innocent people to death on the basis of what Alexis Agathocleous, a lawyer for the Innocence Project, which works to exonerate wrongly convicted prisoners, calls “deeply unreliable” evidence. Nationally, DNA evidence has been used to exonerate at least six people who were convicted of crimes partially on the basis of hypnotically induced testimony, according to data from the Innocence Project, which is now briefing the court against the use of forensic hypnosis in Flores’s case.

If Flores’s appeal is successful and his conviction is overturned, Texas is highly likely to join the 27 states that have already banned the use of forensic hypnosis as a result of the growing expert consensus that it is junk science. (Another six states have no forensic hypnosis case law, leaving its legal status there highly ambiguous.) This would add the momentum of the US’s second most populous state to a nationwide push to scrap the practice. If the appeal fails, Flores’s case could still go to the US supreme court, which could decide to ban forensic hypnosis across the country. But Flores could also lose all his appeals, which might lead to his execution, and entrench the use of forensic hypnosis in states such as Texas.

The way hypnotists describe their art usually depends on what they want hypnosis to achieve. Those who see it as a therapeutic tool talk about it almost like a drug – one that eases physical pain and anxiety, lowers emotional defences and makes the hypnotised person open to seeing their lives in a more positive light. Those who use hypnosis forensically talk about it as if it were a searchlight, able to pick out particular memories in the murky corners of a traumatised mind.

The very things that make hypnosis valuable in clinical circumstances – such as a hypnotised patient’s openness to suggestions from the therapist and the expectation that hypnosis will work – are dangerous when it comes to trying to establish facts in settings such as a courtroom. “Think of hypnosis like a memory pill,” Lynn, who is also a professor of psychology at the State University of New York at Binghamton, told me. “If you believe that after you take this pill your memory will be improved, then, when questioned about whatever you recall, you will be more likely to say: ‘Yeah that was an accurate memory, I’m confident in my recall of that.’ It acts almost like a placebo.”

Hypnosis is difficult to research at scale, but many small studies suggest that the relationship between hypnosis and memory is highly problematic. In 1983, a study at Concordia University in Montreal found that hypnotised subjects tend to be particularly susceptible to the implantation of false memories by hypnotists. In another study, in 2006, Lynn explored the memories of people after the death of Princess Diana. Using a range of memory recall techniques, he asked them to remember what they did on the day she died, and then fact-checked their memories. He found that hypnotised subjects remembered less than those who were not hypnotised and omitted more details. Many studies have also found that hypnosis increases subjects’ confidence in their memories, regardless of whether those memories are accurate or not. This is the case even when the “hypnosis” undergone by subjects wouldn’t be recognised as such by most practitioners. “Simply defining a procedure as hypnosis carries some risk that people’s confidence in their memories will be boosted,” Lynn said.

Many practitioners of forensic hypnosis know that it can create false memories, but it is a risk they willingly take. “More memory, how could that be a bad thing?” said Carol Denicker, a hypnotist in New York state.

Bob Erdody, a hypnosis consultant and retired NYPD officer, told me most of the information obtained in interviews can be corroborated, so false memories get weeded out. His most successful use of hypnosis was with a young man who was able to remember a decal on the window of a car involved in a shooting, which resulted in an arrest. But he also acknowledged that forensic hypnosis could be unreliable: he had consulted on a case in which hypnosis led to a wrongful charge of sexual assault.

There is a deeper problem, though, which is that inaccurate memories are common even in non-hypnotic police interviews. An accumulating body of research shows that the thing almost every investigation relies on to some extent – witness memory – is not good forensic evidence. The Innocence Project has used DNA testing to uncover 367 wrongful convictions; almost 70% of these involved a witness misidentifying the perpetrator.

“There’s still a common lay belief that memory works as a recording device,” said Elizabeth Loftus, an expert in eyewitness identifications at the University of California at Irvine. About half of jurors believe memory works this way, according to a study Loftus conducted in 2006. Partly as a result, juries are strongly compelled by eyewitnesses, especially when those witnesses express a high degree of confidence in their memories. “The confidence expressed by a witness is the single most important factor in persuading jurors that a witness correctly identified the criminal,” Lynn and his colleagues have written. As Gardner put it, “it is way too risky” to use such testimony, “particularly in a state that has capital punishment or life without parole”.

But if memory itself is unreliable, defenders of forensic hypnosis argue, then logically you have a choice: you can either keep forensic hypnosis, or throw out witness statements altogether. “Opponents of the police use of hypnosis, they would have you believe that we don’t know how to get down here to this office tomorrow or what we did yesterday or what I had for supper last night,” said Marx Howell, a former Texas patrolman who, in 1979, created a forensic hypnosis training programme for Texas police and has since trained thousands of officers. “Memory is fallible, but we use memory a lot. It can’t be so fallible that you can’t use it.”

Of course, if memory were entirely reliable, there wouldn’t have been a need for something like forensic hypnosis in the first place.

Forensic hypnosis became popular, in part, because its successes were front-page news. “‘Major Break’ Expected in Mass Abduction” ran the headline of an article on the cover of the New York Times in July 1976, about the buried-alive bus driver who had recalled the licence plate number of his abductors. That case was “the catalyst case for law enforcement use” across the country, said Howell, who led the establishment of Texas’s hypnosis programme three years later. In Los Angeles in the late 70s and early 80s, the police were conducting an average of more than 100 hypnoses per year; the head of the LAPD’s hypnosis programme claimed that three-quarters of these yielded information of value to the case.

By Howell’s lights, the Texas programme was successful: he told me that during the first 10 years of its existence, roughly three out of every four forensic hypnosis sessions in the state resulted in more information. By 1986, more than 800 Texas police officers had been trained in hypnosis. In perhaps the most celebrated hypnosis case in the state in the 80s, the technique was used to solve the murder of a leftwing radical in Austin that had occurred 13 years earlier, in 1967. (The murderer in that case also killed his mother, sawed her body into pieces and scattered them along the highway between Oklahoma and Arkansas.)

But as forensic hypnosis became more widespread, its weaknesses became more evident. In one case in Minnesota in 1980, “a hypnotised person recalled eating pizza in a restaurant that did not serve pizza, seeing tattoos on someone who did not have tattoos and being stabbed with scissors or a knife where there was no physical evidence that a weapon had been used,” Lynn and his colleagues have written.

Thus began “a tidal change” in attitudes towards forensic hypnosis among jurists and psychologists, according to Lynn and his colleagues. In 1981, New Jersey adopted a six-part test for the admissibility of hypnotically induced testimony, designed to minimise the risk that witnesses were having false memories suggested to them by the police. The following year, the supreme court of California ruled that hypnotically induced testimony was inadmissible in court. This dovetailed with the emergence among scientists of the view that memory was reconstructive rather than recording – more like collage than like photojournalism.

In 1987, after a legal challenge by the man convicted of murdering the radical activist (and later his mother), Texas, too, adopted a set of standards for evaluating the admissibility of hypnotically induced testimony; they are known as the Zani guidelines, after the name of the killer. “The problem with hypnosis … is that it tends greatly to facilitate not only the retrieval of genuinely remembered data, but also construction of false but nevertheless plausible data to fill in gaps in true memory,” wrote a judge in the Zani case. “Moreover, once this ‘confabulation’ takes place, neither expert nor jury nor even the witness himself can differentiate historical fact from fantasy.”

Over the next two decades, other states followed in blocking or restricting the use of forensic hypnosis. In 2006, New Jersey abandoned its guidelines and banned the practice altogether after a case in which a hypnotised witness in a sexual assault case identified someone they couldn’t possibly have seen. By this time, even one of the pioneers of forensic hypnosis, Martin Orne, who had created New Jersey’s guidelines, agreed that the practice should be consigned to history. In fact, the guidelines were part of the problem, creating an illusion of reliability: it was like advertising seatbelts for a car without brakes.

Supporters of forensic hypnosis argue that the practice shouldn’t be banned because of a few bad cases. “They threw the baby out with the bathwater,” Howell said of the 2006 decision in New Jersey. But the push to end forensic hypnosis has been part of a broader movement against the use of junk science to convict people. In 2004, in one of the most famous junk science cases, Texas executed Cameron Todd Willingham for the murder by arson of his three children on the basis of scientific techniques which have since been discredited. This ultimately led to the creation of the Texas Forensic Science Commission, which examines junk science, and the junk science statute that is now being used to challenge Flores’s conviction.

Texas’s “forensic commission represents the gold standard” for determining what sorts of evidence should be allowed in court, said Agathocleous, the Innocence Project lawyer. The state has worked its way through a handful of junk science issues, such as the use of bite marks to identify a suspect (now totally debunked) and the practice of matching hairs found at a crime scene to suspects. Forensic hypnosis could be next. But whether the science that could sway the commission will be heeded by the criminal court hearing Flores’s appeal is a separate question. “Hopefully the Texas court understands what we now know,” Agathocleous said.

The hypnosis in the case that put Flores on death row was particularly bizarre. The witness, a Dallas woman named Jill Bargainer, lived next door to the victim. Early on the morning of 29 January 1998, Bargainer thought she saw two white men get out of a yellow Volkswagen Beetle parked in her neighbour Betty Black’s driveway. A couple of hours later, Betty’s husband came home from work to find Betty and their doberman, Santana, shot dead.

Later that day, at the local police station, Bargainer identified the driver of the car in a number of photo arrays. (He turned out to be the boyfriend of Betty’s daughter-in-law and owned a pink and purple VW Beetle with a flame design running down the side.) Five days after that, police asked for Bargainer’s help creating a composite sketch of the passenger, but by this time, she was unravelling. She told them she couldn’t sleep and couldn’t stop shaking, and asked if they could hypnotise her so that she could “relax and do a good composite”, according to subsequent testimony. Bargainer could not recall later how she knew that hypnosis was something they might offer.

The next day, a patrol officer trained in forensic hypnosis hypnotised Bargainer. It was the first and last forensic hypnosis he ever performed. In a video recording of the session, he tells Bargainer to imagine she is sitting in a cinema, holding a remote control; she can use the remote any time she likes to stop the film, or fast forward. Hypnotists call this the “movie theatre technique”. It has often been used to help emotionally traumatised witnesses feel they can control their memories.

Bargainer mentioned a few new details in the course of the hypnosis – the first suspect was holding a beer bottle; the second had brown eyes – but nothing particularly substantive emerged. Then, at the end of the session, the officer told her that she would “be able to recall more of the events as time goes on”. After the hypnosis, she helped police draw a composite sketch of the passenger she thought she saw – a thin caucasian man with long hair.

Police then showed Bargainer a series of photo arrays including images of the person they believed to be the passenger: a heavy-set, brown-skinned, short-haired latino man, who had been caught setting the VW on fire two days after the murder – Charles Flores. But Flores did not match Bargainer’s description of the passenger and she did not identify him at that time.

Eventually, prosecutors gathered enough circumstantial evidence to prosecute Flores anyway. At his trial in February 1999, 13 months after the killing, Bargainer was called as a witness. But after she took the stand, the defence called for a Zani hearing. The Zani guidelines use a minimum of 10 criteria to determine whether the testimony of a previously hypnotised witness should be admissible in court. The criteria include: the interviewer should not be otherwise involved in the case; a recording of the hypnosis should be made that shows everyone in the room at the time of the hypnosis; and no suggestions should be made to the hypnotee.

Despite the fact that Bargainer’s hypnosis violated these three guidelines and a number of the other ones, the judge allowed Bargainer to take the stand. In a shocking reversal of what she had told police during the investigation, she identified Flores, who was sitting at the defence table, as the second man she saw that morning.

Lynn called the identification “astounding”. “I cannot tell you a single time, personally, when I couldn’t recognise something and then 13 months later I was completely positive,” he told a court hearing in the Flores case in 2017. Lynn considered it particularly problematic that the hypnotist told Bargainer she would remember more as time went on.

“The fact that Flores has found some people to be hoodwinked by his media show sounds good and makes for a good article, but is not what happened here,” Jason January, the prosecutor who secured Flores’s original conviction, told me. Several people testified in court that they had seen Flores with the other suspect on the day of the murder, and another testified that Flores had admitted to shooting the dog. January called the murder “an open and shut case”. Bargainer’s inability to identify Flores until the trial did not bother him, he said, because people’s appearance can change and in-court identifications happen all the time. The hypnosis was a way to relax, he said – a “glorified spa session”. He didn’t see any reason that Flores’s conviction should be overturned, or to ban forensic hypnosis in general.

But those supporting Flores, including Agathocleous, believe his case is an extraordinarily compelling example of why forensic hypnosis should be banned. “So many of the different misidentification phenomena all appear” in the Flores case, Agathocleous said. These include the low, early morning light in which Bargainer saw the suspects; the short amount of time she saw them; the fact that she was standing at a significant distance from them; the mismatch between her initial description of the second suspect and Flores; the development of a composite sketch, which is known to compromise eyewitness memory; the use of a suggestive photo array in which Flores stood out; the eyewitness’s failure to identify Flores in that array; and the eyewitness’s exposure to media images of Flores after his arrest. “Then, given the interaction between the unreliable identification and the overlay of hypnosis,” Agathocleous added, “there are very, very troubling questions here.”

While he waits indefinitely for a decision from Texas’s court of criminal appeals, Flores spends a lot of time in his cell on death row, meditating and writing. If he wins his appeal, his case will go back down to a trial court for a new trial, two decades after the first one. In the meantime, the driver of the Volkswagen struck a deal in 2000 after pleading guilty to the murder and indicating the gun used in the crime was his, and has been out on parole for three years. (Under Texas law, multiple people can be found guilty of a murder if it happens in the course of them committing another crime, like the robbery in the Flores case.)

But there is still a high chance that Texas will eventually execute Flores. In a cruel irony, his case has drawn enough attention to the problems with forensic hypnosis that, even if the state does put him to death, it may still ban forensic hypnosis.

One of the key figures challenging the practice is Juan Hinojosa, a Texas state senator who has been involved in fighting the use of forensic junk science since the early 2000s, when he was deeply upset by the execution of Todd Willingham, the man wrongfully convicted and then executed for burning his children to death. “I think quite frankly, we convicted wrongfully an innocent man,” Hinojosa told me. In the wake of Willingham’s execution, he worked to establish the Forensic Science Commission. The goal, he said, was to have forensics “based on some actual research and data, and not just on somebody’s intuition or bias within the criminal justice system”. He also began to read widely about other potentially dubious forms of forensic science, including hypnosis. He has been trying to pass a bill that would make hypnotically induced testimony automatically inadmissible in Texas courts.

In another high-profile case involving forensic hypnosis, Kosoul Chanthakoummane, a friend of Flores’s on death row, is also awaiting a decision from the criminal court of appeals. He was convicted in 2007 for the killing of a real estate agent in McKinney, Texas. A hypnotised witness was also used in this case, alongside bite mark analysis and questionable DNA evidence. The case has so many bits of forensic science gone wrong that Ben Wolff, Flores’s lawyer, calls it a “parade of horrors”. This case, too, could help sway the Texas judiciary against forensic hypnosis.

“The timing is critical,” Agathocleous said of Flores’s case. The US is in the midst of a vast re-evaluation of the validity of many kinds of forensic evidence. In addition to blood spatter analysis, arson science, bite mark analysis and hair microscopy, practices such as ballistics testing and picking suspects out of line-ups using sniffer dogs have all been challenged to varying degrees. Even the validity of matching a suspect’s fingerprints to those found at a crime scene has been called into question. This could aid Flores’s case and the movement to end forensic hypnosis nationwide.

But banning forensic hypnosis opens up bigger questions than those posed by the end of some other forensic techniques. It points to the need for a broader reconsideration of the way that police and prosecutors influence the memories of witnesses and suspects. “Inaccurate memories that eyewitnesses express with any degree of inflated certainty in the courtroom can carry life or death consequences,” Steven Lynn told me. What do we do with this dangerous thing that courts have been relying on since time immemorial, that we need to be able to rely on, even when it proves so fleeting? As lawyers from the Innocence Project put it in a brief in Flores’s case, “memory can be easily contaminated” – just like a crime scene.