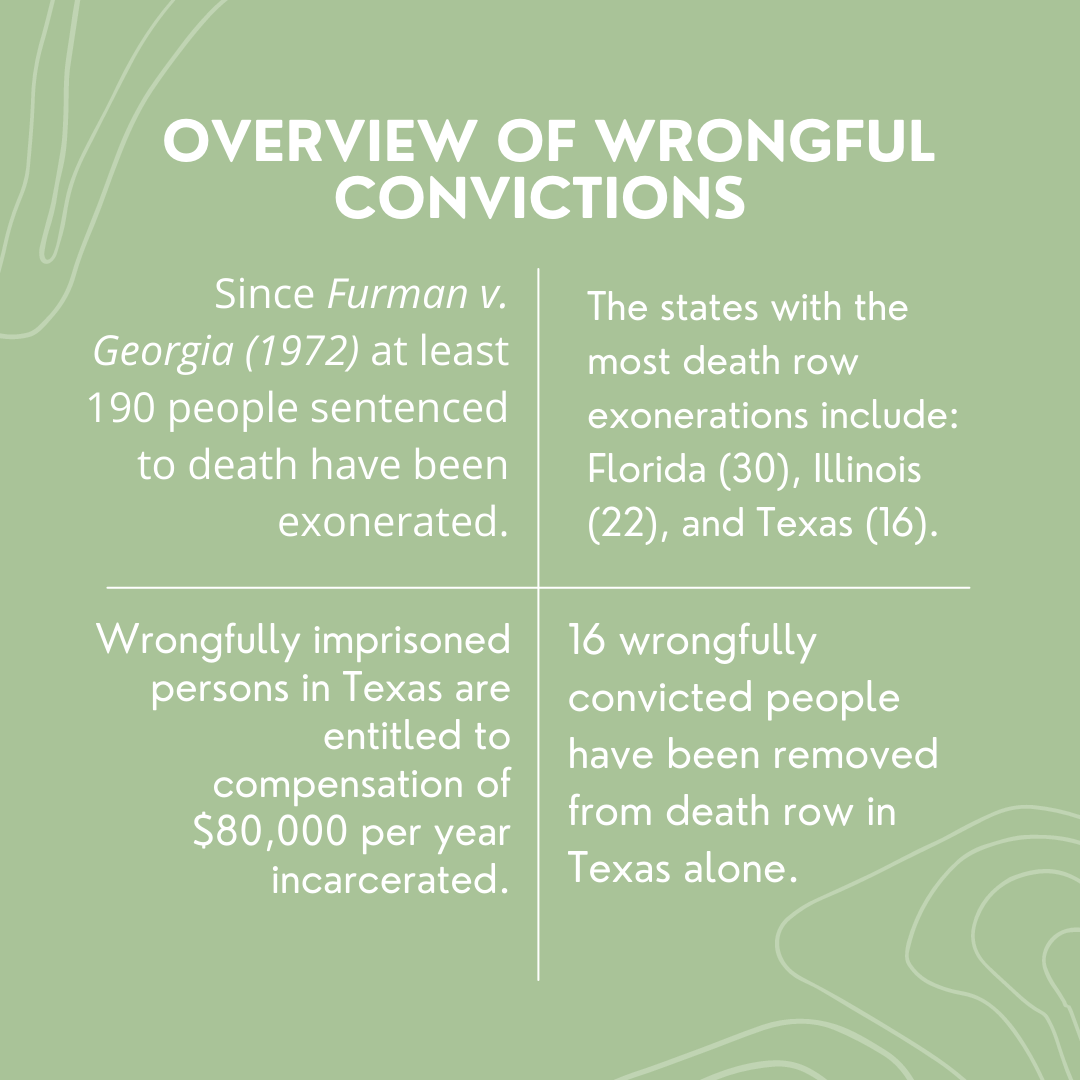

Since 1973, 190 individuals who spent time on death row have been exonerated, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. This includes 16 people who were convicted and sentenced to death in Texas. Read short summaries of their cases below.

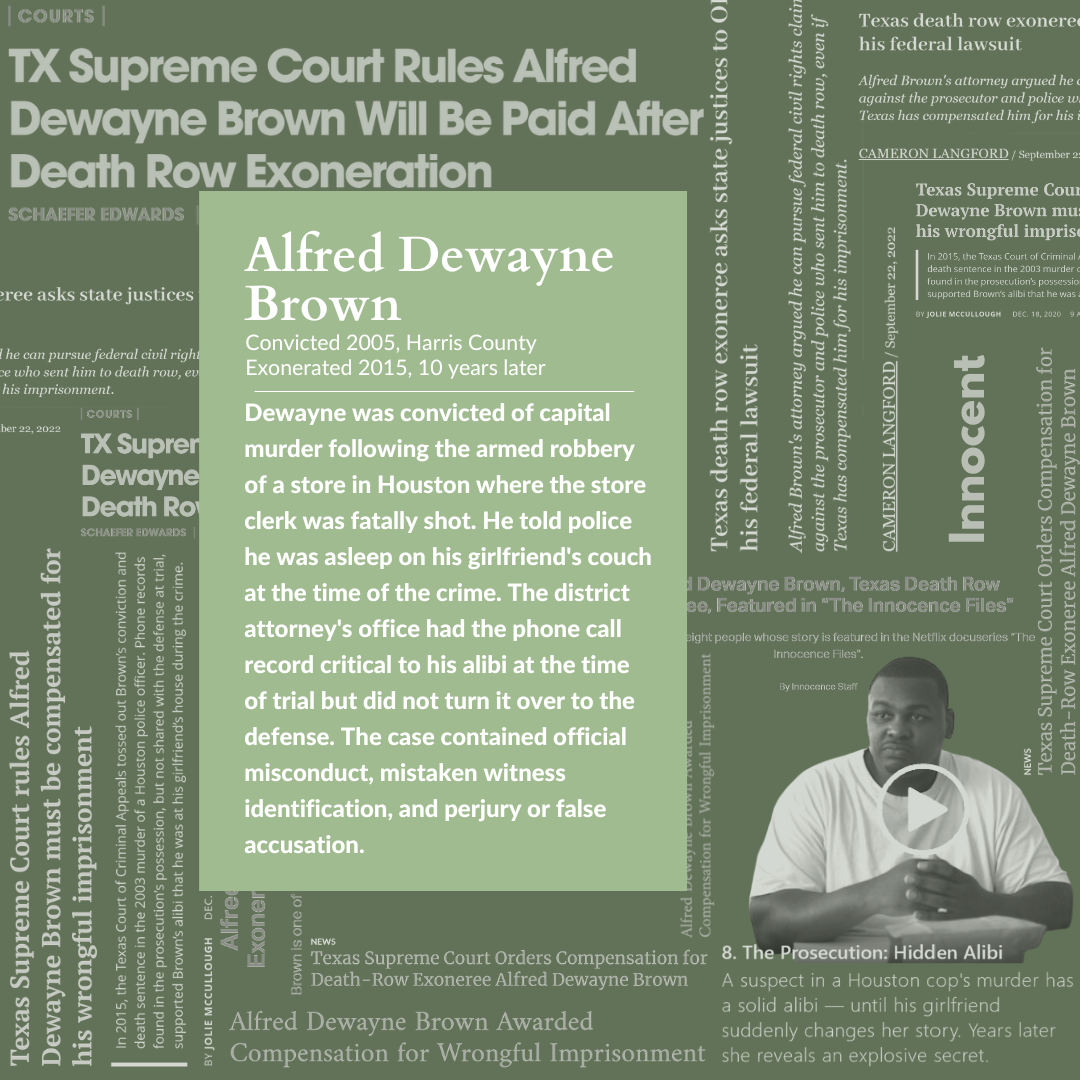

Alfred Dewayne Brown

Convicted: 2005, Charges Dismissed: 2015

On June 8, 2015, the Harris County District Attorney’s Office dismissed capital murder charges against Alfred Dewayne Brown. Brown, who consistently maintained his innocence, spent a decade on death row in Texas for the murders of Houston Police Officer Charles R. Clark and store clerk Alfredia Jones at a check-cashing business in 2003.

Brown’s case is featured in Episode 8 of the Netflix series, “The Innocence Files.”

According to the Houston Chronicle, then-District Attorney Devon Anderson didn’t have enough evidence for a new trial:

“We re-interviewed all the witnesses. We looked at all the evidence and we’re coming up short,” Anderson told reporters. “We cannot prove this case beyond a reasonable doubt, therefore the law demands that I dismiss this case and release Mr. Brown.”

Background on the case

On November 5, 2014, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals overturned Brown’s conviction and death sentence after finding the Harris County District Attorney’s Office withheld material evidence favorable to his case, specifically, a record of a phone call that corroborated his claim that he was at his girlfriend’s apartment the morning the murder took place. In 2013, a homicide detective found a box of phone records in his garage that indicated Brown made the call exactly when he asserted. The file was never shared with Brown’s defense counsel during his original trial.[1] At his trial, Brown’s attorneys presented no evidence of his alibi, and his girlfriend changed her testimony after she was threatened with prosecution by a grand jury.

When prosecutors dismissed the charges against Brown in 2015, they did not declare him “actually innocent”. The State Comptroller used that technicality to deny Brown’s application for compensation for his decade of wrongful incarceration.

On March 1, 2019, the Harris County District Attorney’s Office sought to remedy this and declared Brown “actually innocent” after accepting the findings of a special prosecutor, John Raley, who had been appointed to investigate the case. State District Judge George Powell granted the DA’s motion declaring Brown “actually innocent” on May 3, 2019. In June 2019, however, the State Comptroller once again denied Brown’s application for compensation, leading his attorneys to file a mandamus petition with the Texas Supreme Court.

On December 18, 2020, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that Brown is entitled to compensation for the 12 years he spent behind bars, including a decade on death row, as an innocent man. The Court found the Comptroller exceeded his authority and was wrong to deny Brown the $2 million to which he is entitled based on the length of his wrongful incarceration.

[1] “Appeals court resets murder trial after finding evidence withheld,” Houston Chronicle, November 5, 2014

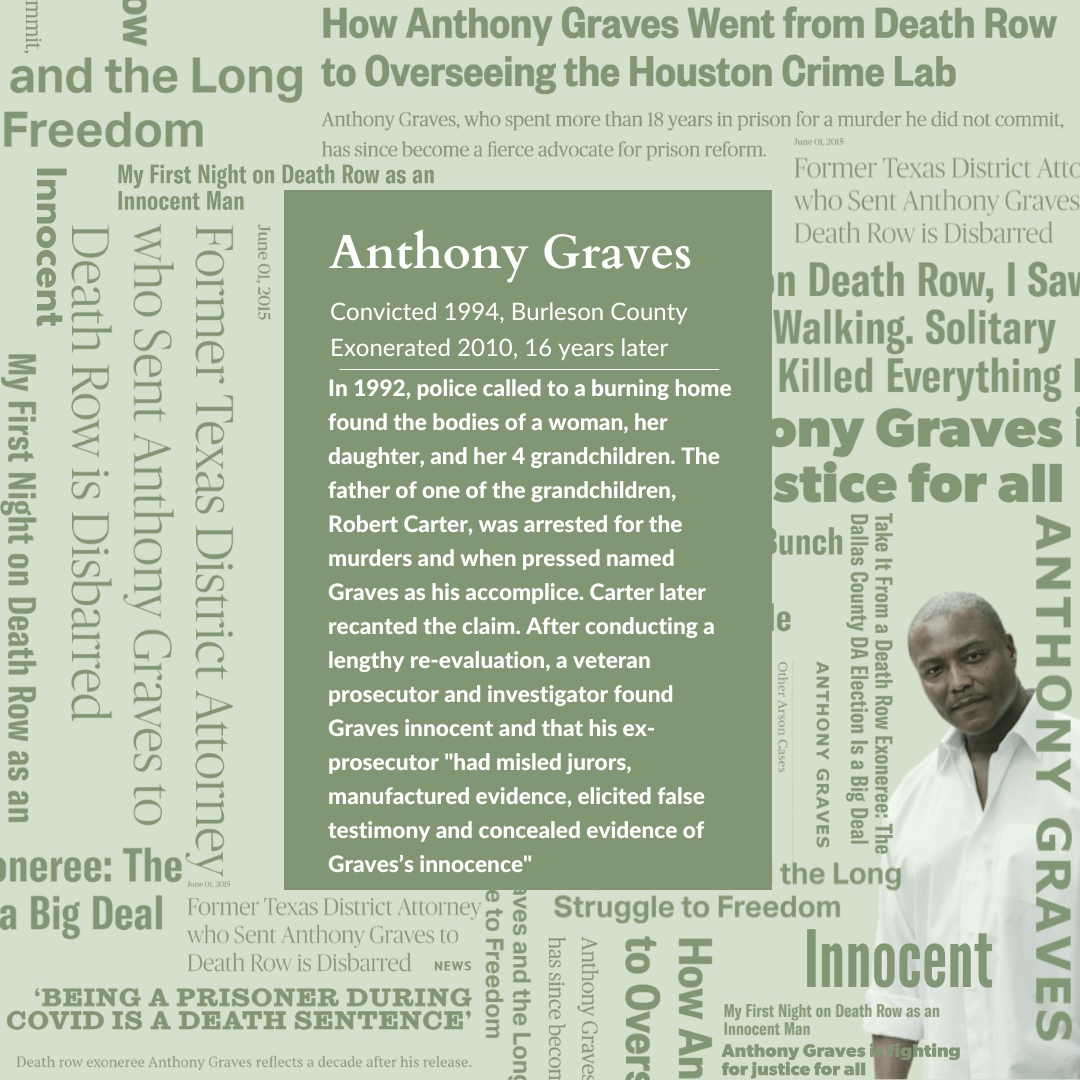

Anthony Graves

Convicted: 1994, Charges Dismissed: 2010

Anthony was released from a Texas prison on October 27, 2010 after Washington-Burleson County District Attorney Bill Parham filed a motion to dismiss all charges that had resulted in Graves being sent to death row 16 years ago.

Graves was convicted in 1994 of assisting Robert Carter in multiple murders in 1992. There was no physical evidence linking Graves to the crime, and his conviction relied primarily on Carter’s testimony that Graves was his accomplice. Two weeks before Carter was scheduled to be executed in 2000, he provided a statement saying he lied about Graves’s involvement in the crime. He repeated that statement minutes before his execution. In 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturned Graves’s conviction and ordered a new trial after finding that prosecutors elicited false statements and withheld testimony that could have influenced the jurors. (Graves v. Dretke, No. 05-70011, U.S. 5th Cir. Mar. 6, 2006).

After D.A. Parham began to reassemble the case and review the evidence, he hired former Harris County assistant district attorney Kelly Siegler as a special prosecutor. Siegler soon realized that making a case against Graves would be impossible: “After months of investigation and talking to every witness who’s ever been involved in this case, and people who’ve never been talked to before, after looking under every rock we could find, we found not one piece of credible evidence that links Anthony Graves to the commission of this capital murder. This is not a case where the evidence went south with time or witnesses passed away or we just couldn’t make the case anymore. He is an innocent man,” Siegler said.(B. Rogers, “Prisoner ordered free from Texas’ death row,” Houston Chronicle, October 28, 2010).

Read “Innocence Found,” January 2011, Texas Monthly.

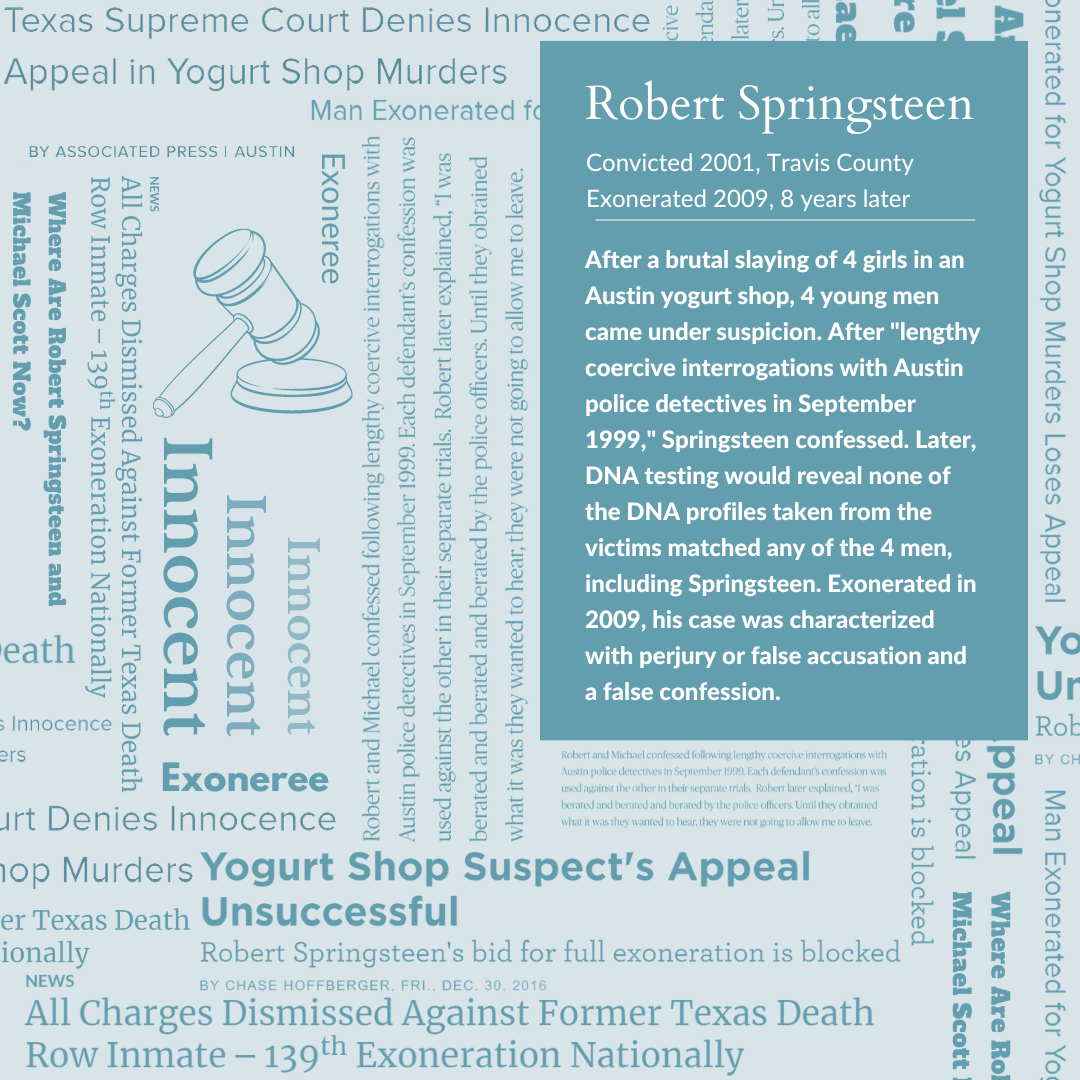

Robert Springsteen

Convicted: 2001, Charges Dismissed: 2009

On October 28, 2009, Travis County, Texas, prosecutors moved to dismiss all charges against Michael Scott and Robert Springsteen, who had been convicted of the murder of four teens in an Austin yogurt shop in 1991. (Springsteen was convicted in 2001; Scott in 2002.) Springsteen had been sentenced to death and Scott was sentenced to life in prison. The convictions of both men were overturned by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals because they had not been adequately allowed to cross examine each other. (See Springsteen v. Texas, No. AP-74,223 (May 24, 2006)).

State District Judge Mike Lynch had released the defendants on bond in June, pending a possible retrial by the state. However, sophisticated DNA analysis of evidence from the crime scene did not match either defendant and the prosecution announced it was not prepared to go to trial. The judge accepted the state’s motion to dismiss all charges. Prosecutors are still trying to match the DNA from crime with a new defendant. “This has been a long time coming,” said Scott, once charges were dropped, “and I’m happy to be here.”

Both Scott and Springsteen implicated themselves at the time of their arrest, 8 years after the crime. However, both claimed that their statements had been coerced by police. The police investigation had been compromised from the start because the building had been set on fire, and thousands of gallons of water were poured on the crime scene before an investigation was carried out.

Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg issued a statement that said in part: “Make no mistake, this is a difficult decision and one I would rather not have to make.”(S. Kreytak, “Charges dismissed in yogurt shop case,” Austin American-Statesman, October 28, 2009; see also J. Vertuno, “Murder counts tossed in Texas yogurt shop slayings,” Associated Press, Oct. 29, 2009).

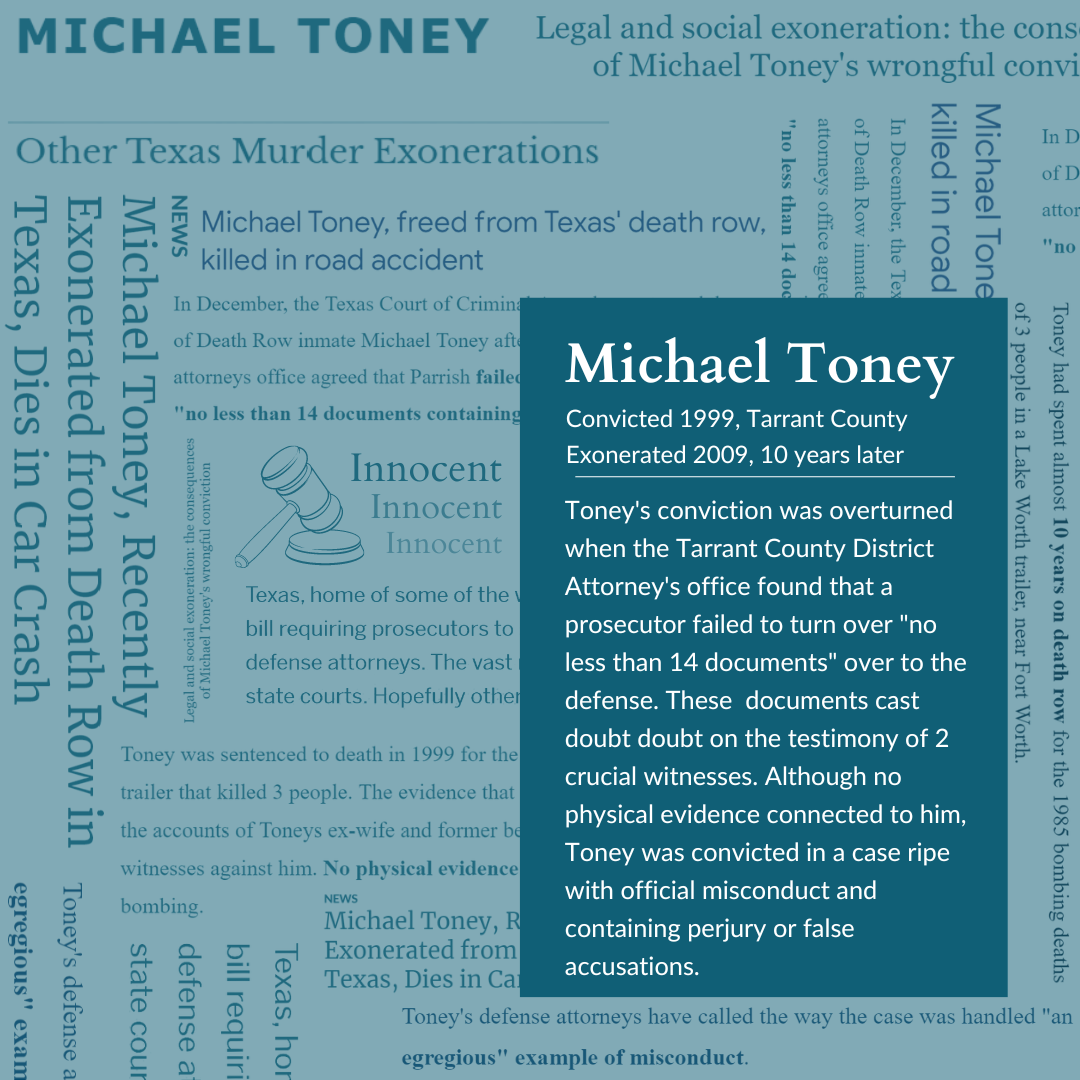

Michael Toney

Convicted: 1999, Charges Dismissed: 2009

Toney was released from jail on September 2, 2009 after the state dropped all charges against him for a 1985 bombing that killed three people. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals overturned Toney’s conviction on December 17, 2008 because the prosecution had suppressed evidence relating to the credibility of its only two witnesses. (Ex parte Toney, AP-76,056 (Tex. Crim. App. December 17, 2008)).

The Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office subsequently withdrew from the case based on the misconduct findings. In September 2009, the Attorney General’s Office, which had been specially appointed to the case in the wake of Tarrant County’s withdrawal, dismissed the indictment against Toney. He had consistently maintained his innocence. The case had gone unsolved for 14 years until a jail inmate told authorities that Toney had confessed to the crime. The inmate later recanted his story, saying he had hoped to win early release.

The state said it is continuing its investigation into the murders. Toney was killed in an automobile accident one month after his release. The state said it is continuing its investigation into the murders.(A. Branch, “Man convicted in bombing dies in wreck 1 month after his release,” Ft. Worth Star-Telegram, Oct. 4, 2009 (including picture); also email from J. Tyler, Texas Defender Service, Oct. 4, 2009)

Michael Blair

Convicted: 1994, Charges Dismissed: 2008

Michael Blair was sentenced to death for the 1993 murder of 7-year old Ashley Estell. In May 2008, following a re-investigation of the case by the Collin County prosecutor’s office, District Attorney John Roach announced that in light of the results of advanced DNA testing and the absence of any other evidence linking him to the crime, Mr. Blair’s conviction could no longer be upheld.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals upheld the decision of the Collin County trial court that:”The post conviction DNA results and the evidence discovered in the State’s new investigation have substantially eroded the State’s trial case against [applicant]. This new evidence in light of the remaining inculpatory evidence in the record, has established by clear and convincing evidence that no reasonable juror would have convicted [applicant] in light of newly discovered evidence. “Although the court recommended that a new trial be granted, the prosecution, in light of the evidence, chose not to pursue a retrial. In a dismissal motion filed in August 2008, prosecutors determined that “this case should be dismissed in the interest of justice so that the offense charged in the indictment can be further investigated.”

All charges against Mr. Blair in this case were dismissed in August 2008. He remains in prison serving out life sentences for other crimes.”Court Dismisses Ashley’s Killer, cites DNA Test,” Associated Press, The Houston Chronicle, September 17, 2008; Ex Parte Michael Nawee Blair, Nos. AP-75,954 & AP-75,955, Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, June 25, 2008 at 3.

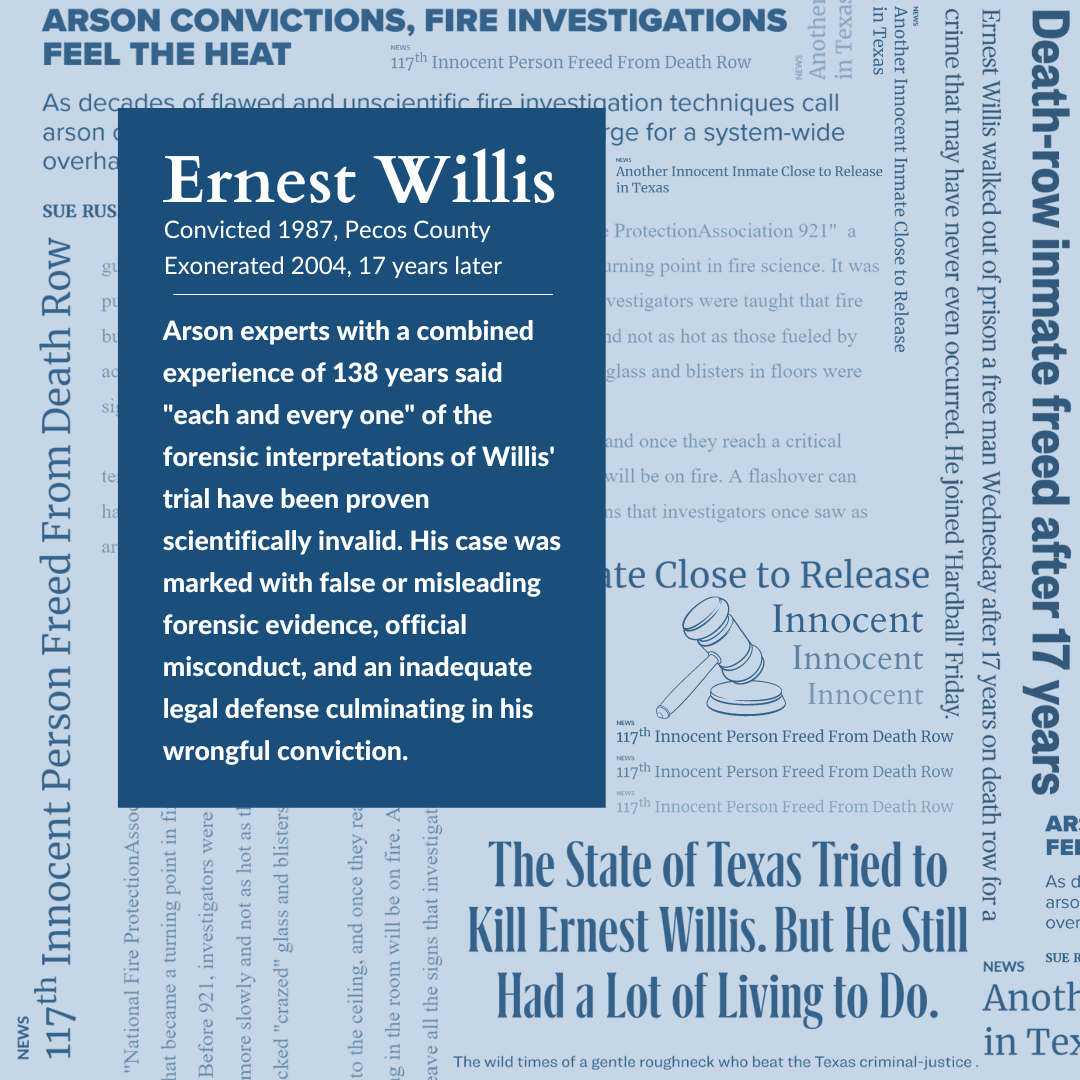

Ernest Ray Willis

Convicted: 1987, Charges Dismissed: 2004

Ernest Ray Willis was sentenced to death for the 1986 deaths of two women who died in a house fire that was ruled an arson. Seventeen years later, Pecos County District Attorney Ori T. White revisited the case after a federal judge overturned Willis’ conviction. (Willis v. Cockrell, 2004 WL 1812698 (W.D.Tex.)) White hired an arson specialist to review the original evidence, and the specialist concluded that there was no evidence of arson.

Willis, who was staying briefly at the house where the fire occurred, escaped from the house. Investigators believed they found an “accellerant” in the carpet. Officers at the scene of the blaze said that Willis had acted strangely, and prosecutors had Willis arrested. Despite limited evidence, Willis was indicted for murder and arson. Prosecutors used Willis’ dazed mental state at trial – the result of state-administered medication – to characterize Willis as “coldhearted” and as a “satanic demon.” Willis’ court-appointed lawyers, one of whom later surrendered his law license following drug charges, offered little defense. The attorneys spent a total of three hours with Willis, and as a result, Willis was found guilty and sentenced to death.

The state’s new arson specialist revealed, however, that the “accelerant” initially suspected of causing the fire was in fact “flashover burning,” consistent with electrical fault fires. U. S. District Judge Royal Ferguson held that the state had administered medically inappropriate antipsychotic drugs without Willis’ consent; that the state suppressed evidence favorable to Willis; and that Willis received ineffective representation at both the guilt and sentencing phases of his trial.

He ordered the state to either free Willis or retry him. The state attorney general’s office declined to appeal, and prosecutors dropped all charges against Willis. White, whose predecessors prosecuted Willis, said that Willis “simply did not do the crime. … I’m sorry this man was on death row for so long and that there were so many lost years.” (Los Angeles Times, October 7, 2004). Willis, who had no prior record, was released on October 6, 2004 with $100, ten days of medication, and the clothes on his back. (Los Angeles Times, Houston Chronicle, and Dallas Morning News, October 7, 2004).

Read “Death Isn’t Fair” by Micheal Hall in Texas Monthly

Read “After 17 Years…” by Maureen Balleza in The New York Times

Ricardo Aldape Guerra

Convicted: 1982, Charges Dismissed: 1997

Guerra was sentenced to death for the murder of a police officer in Houston. Federal District Judge Kenneth Hoyt ruled on Nov. 15, 1994 that Guerra should either be retried in 30 days or released, stating that the actions of the police and prosecutors in this case were “outrageous,” “intentional” and “done in bad faith.” He further said that their misconduct “was designed and calculated to obtain . . . another ‘notch in their guns.'” (Guerra v. Collins, 916 F. Supp. 620 (S.D. Texas, 1995)).

Judge Hoyt’s ruling was unanimously upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals. (Guerra v. Johnson, 90 F.3d 1075 (5th Cir. Tex. 1996)). Although Guerra was granted a new trial, Houston District Attorney Johnny Holmes dropped charges on April 16, 1997 instead. Guerra returned to his native Mexico. (New York Times, 4/17/97).

Read “Mexican Long Held…” in The New York Times

Muneer Deeb

Convicted: 1985, Acquitted: 1993

Deeb was originally sentenced to death for allegedly contracting with three hitmen to kill his ex-girlfriend. The hitmen were also convicted and one was sentenced to death. Deeb consistently claimed no involvement in the crime.

Deeb’s conviction was overturned by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in 1991 because improper evidence had been admitted at his first trial. With an experienced defense attorney, Deeb was retried and acquitted in 1993. (Deeb v. State, 815 S.W.2d 692 (Tex. Crim. App. 1991) and The Dallas Morning News, 11/4/93).

Federico M. Macias

Convicted: 1984, Charges Dismissed: 1993

Macias was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a man during a burglary. Macias was implicated by a co-worker, who in exchange for his testimony was not prosecuted for the murders, and from jail-house informants.

Post-conviction investigation by pro bono attorneys discovered substantial evidence of inadequate counsel. A federal district court ordered a new hearing finding that “[t]he errors that occurred in this case are inherent in a system which pays attorneys such a meager amount.” Macias’s conviction was overturned and a grand jury refused to reindict because of lack of evidence. (Marinez-Macias v. Collins, 810 F Supp. 782 (W.D. Tex. 1991), National Law Journal, 5/20/96, and University of Massachusetts Alumni Magazine, Spring 1994).

Read “The Difference a Million Makes” by Adam Cohen in Time Magazine

Clarence Brandley

Convicted: 1981, Charges Dismissed: 1990

Brandley was awarded a new trial when evidence showed prosecutorial suppression of exculpatory evidence and perjury by prosecution witnesses. An investigation by the Department of Justice and the FBI uncovered more misconduct, and in 1989 a new trial was granted.

Prior to the new trial, all of the charges against Brandley were dropped. Brandley is the subject of the book White Lies by Nick Davies. (Ex Parte Brandley, 781 S.W.2d 886 (Tex. Crim App. 1989),The Dallas Times Herald, 10/2/90, and Washington Post, 2/1/95).

John C. Skelton

Convicted: 1983, Acquitted: 1990

Despite several witnesses who testified that he was 800 miles from the scene of the murder, Skelton was convicted and sentenced to death for killing a man by exploding dynamite in his pickup truck. The evidence against him was purely circumstantial and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found that it was insufficient to support a guilty verdict. The Court reversed the conviction and entered a directed verdict of acquittal. (Skelton v. State, 795 S.W.2d 162 (Tex. Crim. App. 1989) and The Dallas Morning News, 10/25/90).

Randall Dale Adams

Convicted: 1977, Charges Dismissed: 1989

Adams was convicted of killing a Dallas Police officer and sentenced to death. After the murder David Harris was arrested for the murder when it was learned that he was bragging about it. Harris, however, claimed that Adams was the killer. Adams trial lawyer was a real estate attorney and the key government witnesses against Adams were Harris and other witnesses who were never subject to cross examination because they disappeared the next day.

On appeal, Adams was ordered to be released pending a new trial by the Texas Court of Appeals. The prosecutors did not seek a new trial due to substantial evidence of Adam’s innocence. Adams case is the subject of the movie, The Thin Blue Line. (Ex Parte Adams, 768 S.W.2d 281 (Tex. Crim App. 1989), Time, 4/3/89, and ABA Journal, 7/89).

Bonnie Erwin

Convicted: 1985, Charges Dismissed: 1987

In 1985, Bonnie Erwin was sentenced to death on Smith County. During his trial, a witness was subpoenaed but did not appear in court. Prosecutors failed to seek testimony from the witness, who would have corroborated Erwin’s story and implicated his co-defendant, who had blamed Erwin for the crime. Erwin’s conviction was vacated in 1987 due to the trial court’s refusal to issue a writ of attachment to secure the witness’s testimony. State prosecutor declined to retry Erwin, dismissing all charges. The case included official misconduct and perjury or false accusations.

Vernon McManus

Convicted: 1977, Charges Dismissed: 1987

After a new trial was ordered, the prosecution dropped the charges when a key prosecution witness refused to testify.

Justin Cruz

Convicted: 1984, Charges Dismissed: 1985

In 1984, Justin Cruz was convicted and sentenced to death based on false testimony. Aside from the statements of Robert Williams, no direct evidence linked Cruz to the crime. Cruz was acquitted in 1985 by the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals which ruled that the evidence was insufficient to convict him after William’s statements were deemed that of an accomplice. A defendant may not be convicted based on an accomplice’s testimony if there is no other corroborating evidence. The case included official misconduct, perjury or false accusations, and insufficient evidence.

Claude Wilkerson

Convicted: 1979, Charges Dismissed: 1983

Claude Wilkerson was convicted in 1979 for a robbery and murder that occurred at a Houston jewelry store. During interrogation, Wilkerson invoked his right to an attorney, but the interrogation was unconstitutionally reinitiated. His conviction rested on a confession that violated many of his constitutional rights.

Wilkerson’s conviction was vacated in 1983 by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals when it ruled that the trial court erred on admitting statements taken illegally be the police without an attorney present. A prosecutor told the Associate Press there was no longer sufficient evidence to prove guilt and the charges were subsequently dropped. The case included official misconduct and false confession.